[This essay continues from an earlier post.]

The last point to consider from Milton’s (Lewis’) schema is the subject. Milton says, “And lastly what K[ing] or Knight before the conquest might be chosen in whom to lay the pattern of a Christian Heroe.” Here Milton seems to refer merely to who the central character is to be, as he then says how Tasso had to choose between Godfrey or Belisarius or Charlemagne. If that is all that is meant, then have already our subject for One Piece: It is Monkey D. Luffy who is going to be the King of the Pirates. Though he is not a king, it is clear that he intends to be, so he hits that mark. He is no “Christian Heroe,” but of course Milton was considering the subject for a poem in his own language, for his own time and place.

Lewis seems to mean more when he speaks of subject and dedicates two chapters of his Preface to Paradise Lost to the subject of Primary Epic versus Secondary Epic. By Primary Epic, he has in mind the two works of Homer and Beowulf. And he says that these do not have the great subject that we now consider proper to an epic. Homer’s epics are not about the Trojan War or about the fate of nations, but they are about personal matters: It is Odysseus’ journey after the Trojan War that is the subject; it is the wrath of Achilles, and the War is merely the occasion and context for this wrath. There is something unchanging about the world of Homer. Sometimes people are happy and sometimes they are not. And he sees this same sort of attitude in Beowulf.

It is with Virgil and the Secondary Epic that the epic subject comes into maturity. The Aeneid traces the journey of a single hero, but it is a poem about the beginning of Rome. Though it is only one legend, it contains the present and all the centuries that intervene. I believe I heard Johnson say that Homer is the better poet but the Aeneid is the better poem. This seemed odd at the time, but Lewis does a good job in showing the Aeneid makes the poems of Homer seem like they were written for boys by comparison.

So now we turn back to One Piece. The first point to notice in contrast with any of the epics considered by Lewis: The world of One Piece has no connection whatsoever with our history or our geography. It has a history and a geography, but they are entirely unconnected with ours. Whether Homer invented his gods or merely turned them into his characters, it is plain that the events in his stories take place somewhere between Greece and Asia Minor. When we get to Virgil and Tasso, their epics bear a historical connection to their own nations and even make mention of their own rulers.

When did it ever become acceptable to invent an entire world? Even Lewis puts Narnia on the other side of a wardrobe in London. Even Tolkien makes his Middle-earth the imagined past of our world. I have consumed so much fantasy and fiction that I do not even think it strange that a story’s setting would be entirely fictional, but it begins to seem novel as I look at the history of the epic.1

All of that being said, is our pirate epic more like the Primary or Secondary Epic in its subject? I will argue that it has more in common with the Primary Epic.

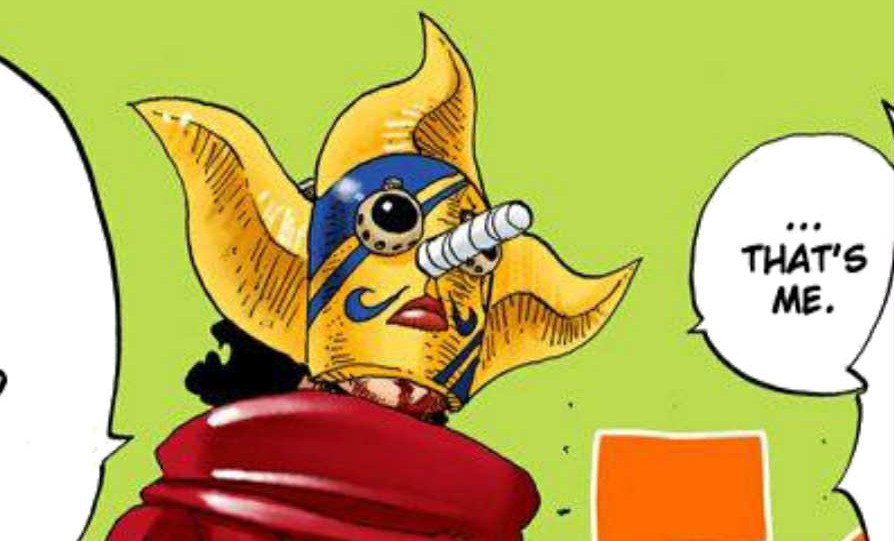

First, as stated, it is the story of Monkey D. Luffy, the man who is going to be the King of the Pirates. Yes, there are many grand themes in this story. The quote from Gold Roger in chapter 100 sums them up well: “These things cannot be stopped. An inherited strength of will. One’s dreams. The ebb and flow of the ages. As long as people hunger for freedom…these things will exist.” But the character Luffy does not care about these things. He cares about his own dream. He cares about his own freedom. He cares about his own friends. This comes out many, many times, but most clearly in the Summit War. The most powerful forces are about to clash, and Luffy is there in the midst of it, running past all of it, all for the sake of a single individual. This is Achilles and Patroclus. Throughout the story, Luffy will fight pirates and marines, he will befriend pirates and marines. He has no allegiance beyond his own aim. Many will rally to his cause, but he binds himself to no cause other than his own. If he puts everything on the line for a member of his crew, it is because he cannot become the Pirate King without him or her.

Second, the world has a cyclical rather than an historical character. Now don’t get me wrong: There are dates and timelines and eras, to be sure. But the more things change, the more they stay the same it seems. We see the parallel between Luffy and Roger twenty years before, or between Luffy and Joyboy 800 years before. We see Noland and Usoland. We see this Buster Call and that Buster Call.

Third, it does not have an obvious moral doctrine. In the Lesser Hippias of Plato, the discussion is about whether the Iliad or the Odyssey is the better poem. Hippias argues that Odysseus is less virtuous than Achilles, and therefore his poem is worse. Socrates does not seem convinced by this argument, and neither am I. For all the beauty of these works, they are both morally frightening. This is in contrast with Virgil where duty and piety are central. In One Piece, certainly some characters and actions are portrayed as straightforwardly evil (e.g. Doflamingo, Spandam, so many Celestial Dragons). Some are unambiguously good (e.g. Dalton and so many of the princesses). But it doesn’t seem to be about that. Nearly all of the characters are pirates, and so they steal and fight and drink. Some pirates are better or worse. Some marines are better or worse. But it is not a story about “being good” and Luffy, though he does not want to see people starve, is very firm in rejecting the title “hero.”

Fourth, it is for boys. One Piece is a shonen manga. This word “shonen” does not describe a genre but a demographic: boys. I began reading it when I was a boy (probably 2004). Given that many of his readers started it 20 years ago, I am sure Oda expects that a large proportion of his audience are now men (or ought to be), but it is still a shonen manga.2 Lewis says, “Any return to the merely heroic, any lay, however good, that tells merely of brave men fighting to save their lives or to get home or to avenge their kinsmen, will now be an anachronism. You cannot be young twice.” But indeed, with One Piece, we become young again.

This is all I have on this subject for now. One Piece is one of my most favorite works in any medium ever produced. I will sometimes be driving down the road and think of a scene and my eyes will water. Immediately after finishing the anime in 2022, it was not long before I began rewatching certain arcs, and have probably rewatched half of it since then. I have not read the entire manga, but I intend to, and I keep up with the latest releases. In the future, I want to read more about poetry and story-telling and how the principles laid down in centuries ago apply to this work of art. Elsewhere, I have written on anime in light of Aristotle’s Poetics, and so I intend to eventually complete that work and post it here, especially if these posts sparked any interest at all.

I looked at the Wikipedia article for “Worldbuilding” and found this idiotic line: “One of the earliest examples of a fictional world is Dante's Divine Comedy.” Nonsense! He is putting into images the very strata of our own world. Each layer is even peopled with every sort of historical figure you can imagine!

In contrast to One Piece, there are some manga that made the transition from shonen (boys) to seinen (young adult). JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure fits in this category, shifting its demographic in a way that reflects the aging of its readers.