In C.S. Lewis’ Preface to Paradise Lost, he considers the importance of Form in a poetic work. He cites a maxim: Materia appetit formam ut virum femina. The matter is found in the poet and the form is the kind of poem, something pre-existing which gives shape to what is in the mind of the poet. It is from the union of these that a work is produced. Since he finds the matter (Milton’s own life) sufficiently considered and known, he devotes himself to the form. From what Milton says in his Reason of Church Government, Lewis organizes the following schema of available forms:

Epic.

Ia. The diffuse Epic [Homer, Virgil, Tasso]

Ib. The brief Epic [the Book of Job]

IIa. Epic keeping the rules of Aristotle.

IIb. Epic following nature.

III. Choice of subject [‘what king or knight before the conquest’]

Tragedy.

a. On the model of Sophocles and Euripides.

b. On the model of Canticles or the Apocalypse

Lyric.

a. On the Greek model [‘Pindarus and Callimachus’]

b. On the Hebrew models [‘Those frequent songs throughout the Law and the Prophets’].

The way he considers Biblical models alongside classical models is a worthy consideration in itself, but the purpose of this post is to see One Piece along the lines laid out here. Given that Lewis finds it worth the time to delineate the form of a poem such as Paradise Lost, which is universally understood to be an epic, it seems just as worthy to consider how these categories apply to works that are not usually scrutinized in such a manner. We will consider each distinction under epic in turn.

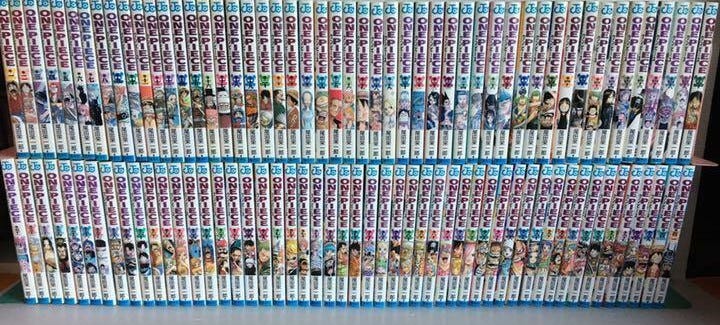

First as to length, whether brief or diffuse. Lewis gets sidetracked by the distinction between Biblical and classical, and so does not actually consider this distinction well. It is not clear how important it could be, but the difference is noticeable. The brief epic of Job is ~12,000 words in Hebrew (~18,000 in KJV), whereas the diffuse ones are significantly longer (Iliad is 150,000; Aeneid is 63,000; Gerusalemme Liberata is over 120,000). One Piece certainly belongs to the diffuse sort, being even longer in its telling than any of these. At the time of drafting, there are 111 printed volumes, and the television adaptation is at 1133 episodes. Though not the longest manga series out there, it takes longer than, say, the Aeneid to get through all of it. Despite the illustrations that fill many pages and the unduly stretched-out episodes of some arcs, it remains a lengthy tale with the scope of a diffuse epic. I am uncertain to what extent length affects the very form of a thing, especially such a thing as poetry. But, at the very least, it affects how the work is received. It took me nearly all of 2022 to watch One Piece. Some weekly readers have spent over 25 years receiving this tale a piece at a time. This is very different from sitting through a movie screening or a night at the opera. Just as scholars acknowledge that Homer’s works were generally not recited in one go, but required multiple hearings to get through, so this work requires an extension of time, a multitude of returns to take in the whole.

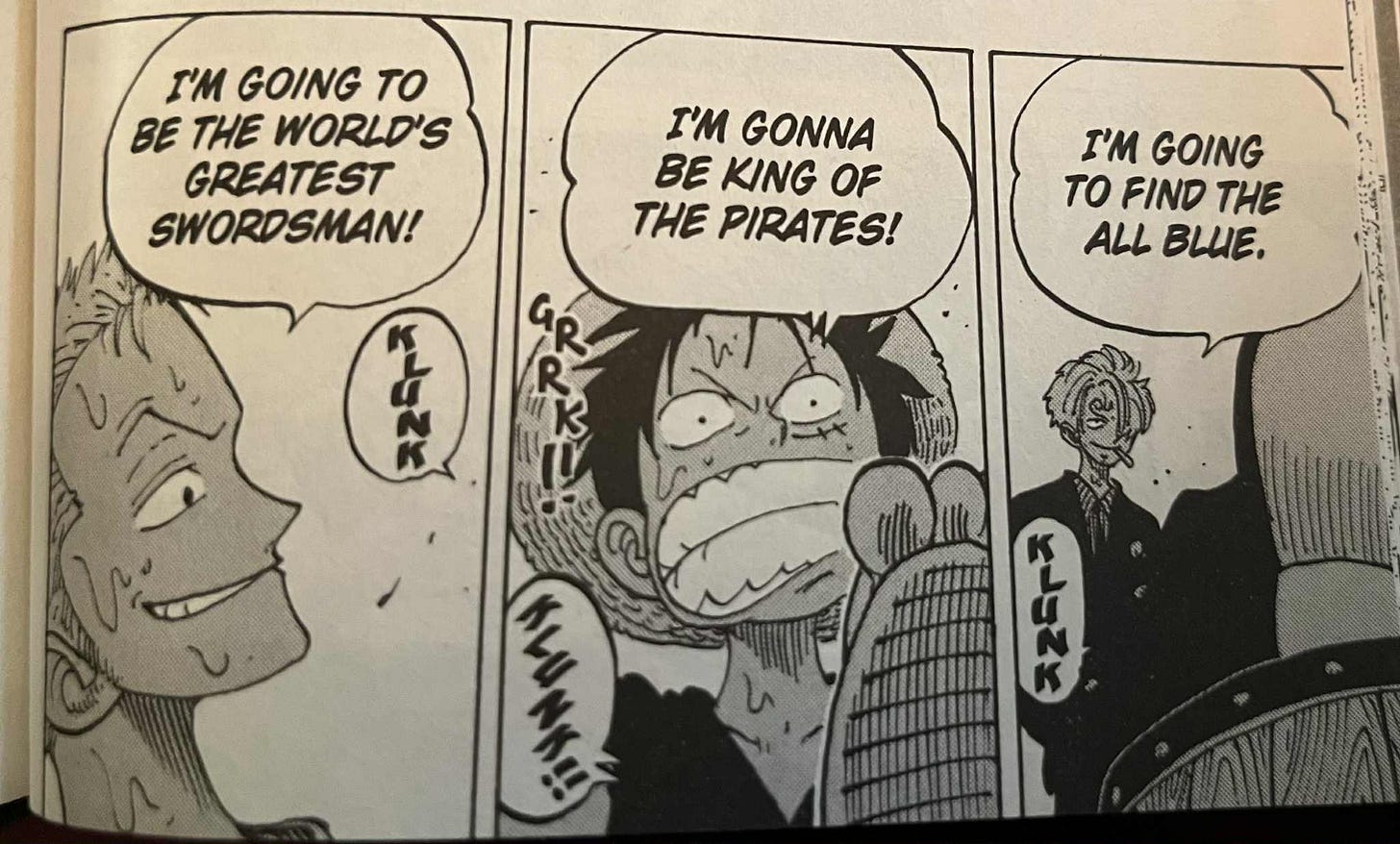

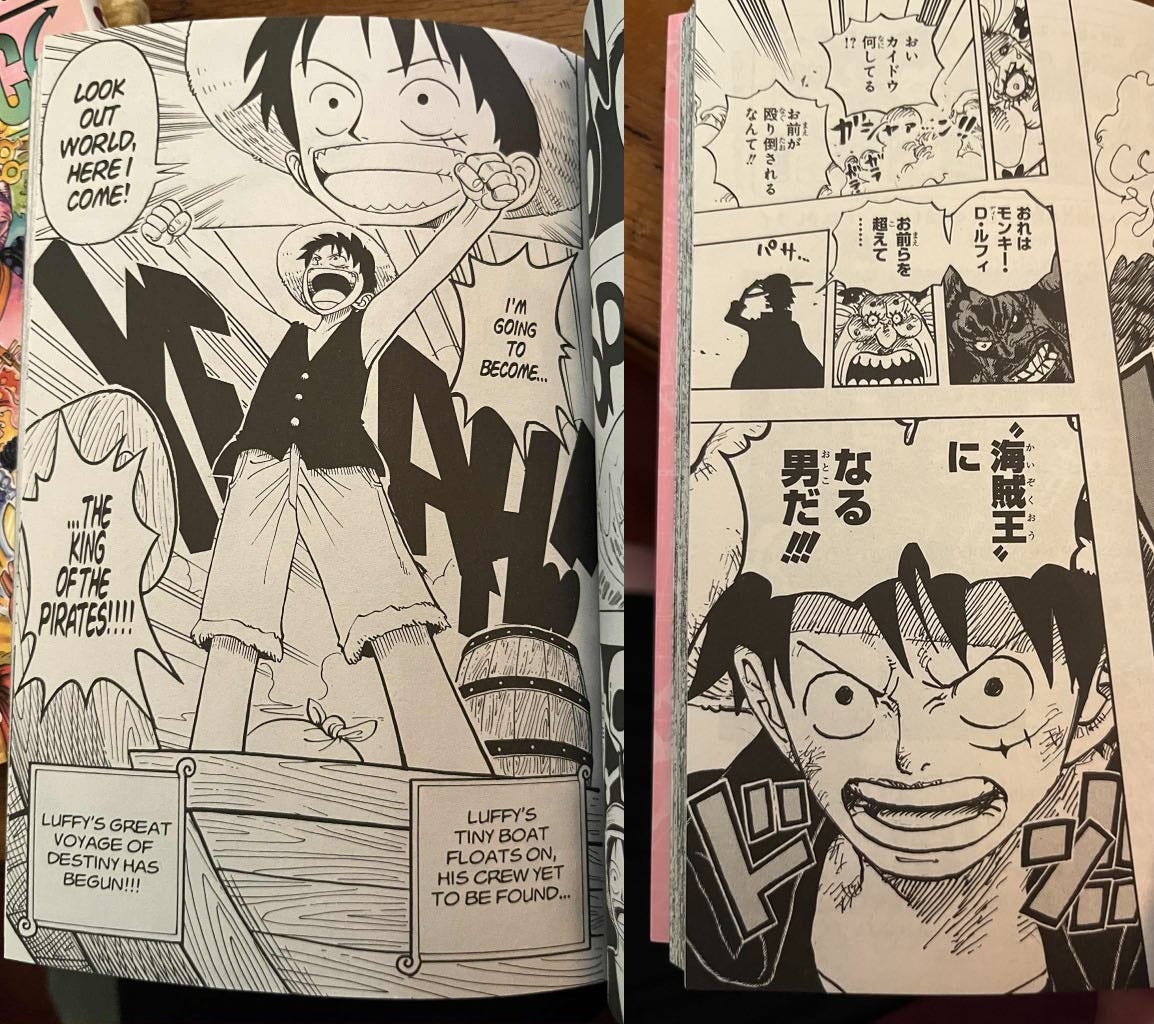

The next distinction is as to whether an epic is “keeping the rules of Aristotle” or is “following Nature.” Lewis spends some time teasing this out and concludes that the rules of Aristotle would have an epic portray one single action, whereas it is more according to Nature (and according to the tastes of knights and ladies) to present a series of episodes, each with its own plot and theme.1 Now, even though One Piece is released in chapters and episodes, and these can be organized in arcs, I would argue that the plot of the work is one single action. There is a man named Monkey D. Luffy who will become the King of the Pirates. He will do this by finding the One Piece. This is where the story begins, this is a point from which it never deviates, and every single episode is connected to this single action. After the end credits of each episode, at the end of the preview, we always hear the protagonist say the same line: 俺はルフィ!海賊王になる男だ!. My primitive Japanese knowledge is sufficient to translate: “I am Luffy! The man who will become the Pirate King!”

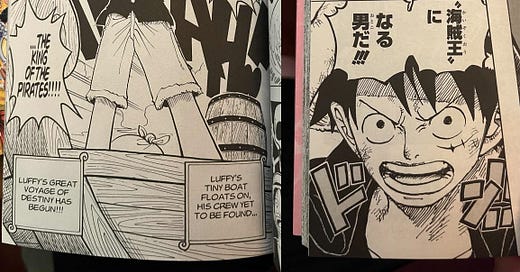

I pick up the first volume now to see that this is firmly established in the first chapter. Now, if we look at the first words of an epic, these often tell us the subject. The Iliad starts with “Wrath,” and so the epic is the story of Achilles’ rage, its beginning, middle and end. The Odyssey starts with “The man, O Muse, inform, that many a way / Wound with his wisdom to his wished stay,” and so our epic is about this man Odysseus on his way home. One Piece begins with the words, “Gold Roger, ‘the King of the Pirates,’ had achieved it all.” There is no invocation of a muse, as with Homer, but we see the man who (in context) set the entire world of the series moving and the title that drives the entire story. By the end of the chapter, we see the moment when a child Luffy declares, “I’m gonna be king of the pirates!!!” and then the chapter ends 10 years later with that same declaration, “I’m going to be king of the pirates!!!!” In the second chapter, Luffy meets another character and declares his intention, and this character (completely incredulous) tells us, the audience, everything it means to become the Pirate King, every sort of obstacle that stands in the way, and so gives Luffy occasion to respond with all he is willing to do for this end. In chapter 923, this is how Luffy introduces himself.

One of the challenges in attempting to explore the form of One Piece is that it is not yet complete. Now for other series, this poses an insurmountable problem in giving a unified account of the work (Hunter x Hunter and Berserk as two examples; one is more cheerful than the other, but in neither case is it clear how it should end). But for One Piece, the action is Luffy becoming the King of the Pirates. Whatever other loose ends exist, whatever mysteries remain, this is our story. Oda has supposedly stated that he knows how the story ends and his closest editors know as well, so that the ending will arrive. But internal evidence defends this as well. Chapter 99 is titled “Luffy Dies” and puts him in a doomed situation. Luffy is on the very scaffold where the first King of the Pirates died and, as a blade is put to his head, he shouts, “I am going to be the King of the Pirates!!!!” (Note: I am accurately putting the number of exclamation marks in my edition.) His crew tries to rescue him and in the last second, he accepts his fate, calling on his crew with a smile and these words: “Sorry. I’m a goner. Hee!!” And… lightning comes from the sky, engulfs the scaffold in flames, and he stands up, free and unharmed!! “Ha ha ha ha! I’m alive. Lucky me.” A benevolent antagonist extrapolates the meaning of all this for us: “Twenty-two years ago, another man laughed on that very spot. He was Gold Roger, King of the Pirates!!! […] It’s as though some kind of force is willing this man’s survival!!!”2

An objection might be leveled here that One Piece is actually the episodic sort of epic. Beyond the obvious episodes, are there not cleanly divided arcs? And indeed, haven’t these arcs been abbreviated into stand-alone films which thus confirm this theory? I answer that One Piece is no more episodic than the Odyssey of Homer. Both of them involving a sea journey, the comparisons are very easy to make. When we look at the Odyssey, we see a single narrative that is told across many islands. The events on each island could form their own stories, to be sure, but they are all crafted to be part of one greater whole. The arcs of One Piece are also typically distinguished by where the crew finds itself, and yet this diversity of place is not sufficient to divide the unified story. The Odyssey has back stories and retelling, just as One Piece has its (rather noteworthy) backstories. The crew that accompanies Odysseus changes at each step of the narrative, and so the journey of One Piece is marked by significant alterations to the crew. Some individual events are remarkably close: Luffy alone on the Island of Women reminds one of Odysseus isolated with Calypso; the disguised homecoming at Sabaody has something of the importance of Odysseus’ nostos; the dangers found in the Sirens or in Scylla and Charybdis have their parallels; Impel Down is reminiscent of the Underworld visit, if not of the Inferno of Dante.

Beyond comparisons such as these, the internal evidence comes in the difficulty of delineating where the arcs begin and end. If we just look at the first East Blue Saga, we see the lines overlap. Nami is introduced the second arc, takes off in the fourth arc, and then is central to the fifth arc. The fourth arc doesn’t just set up the fifth arc, but it introduces a character incomparably stronger than anyone scene up to the point. Dracule Mihawk appears here, then again briefly in 100 chapters, and then again over 300 chapters later. His first appearance serves to let us gauge the protagonists against the wider world. It serves some function in that arc taken by itself, but only makes sense against the larger action of the story. Mihawk only departs after Luffy declares his ever-repeated aim, and Zoro yells, “From now to the day I beat him to become the greatest swordsman…I will never…lose again!!!! Got a problem with that…King of the Pirates!!?”3

There are countless instances that confirm the unity of the story across these arcs. The Summit War flows seamlessly from its three preceding arcs and is followed by an arc that only lends it more weight. Everything in the New World seems to build up the Wano Arc such that you have to start 250 chapters earlier to see its unique characters are introduced, but some groundwork is laid a further 200 chapters before that when Wano is first mentioned (chapter 450).4 Furthermore there are arcs that simply do not work by themselves: Loguetown, Jaya, Sabaody Archipelago, Reverie. Not one of these arcs could serve as a stand-alone film. They are typically short, but reveal the wideness of the world against which the action of the story is placed. (Also: I think the single-arc standalone movies are failures. Without everything that precedes and follows, the emotional weight is not present. Katharsis does not arrive.)

All of this is to say that, according to Milton (as Lewis understands him), One Piece is an epic that follows the rules of Aristotle. For all of its arcs, it portrays one single action, and the narrative never fails to remind the reader of this point of unity.

[This essay will continue in a subsequent post. Please share any thoughts!]

Lewis refers to Tasso’s Discourses on the Heroic Poem, where he says that his father’s Aristotelian epic led to empty auditoriums. This brought him to conclude that people much prefer the episodes. I have not read Tasso’s epic, but I’m certainly tempted to read this work on poetics.

Continuing from here, chapter 100 (titled “The Legend Begins”) starts with a lengthy quote from Gold Roger, King of the Pirates: “These things cannot be stopped. An inherited strength of will. One’s dreams. The ebb and flow of the ages. As long as people hunger for freedom…these things will exist.” The rest of the chapter is silly escape, but we then see each member of the crew state their dream as they finally enter the Grand Line. It is a very tidy way to wrap up the first 100 chapters. One wonders if there is any careful crafting of the chapter numbers with their titles. Chapter 1 is “Romance Dawn”; Chapter 100 is “The Legend Begins”; Chapters 999 with 1000 are ”The Sake I Brewed to Drink with You, Straw Hat Luffy.”

Chapter 52, “The Oath”

It is worth noting that the Wano Country Arc is the only one in which Oda himself gives divisions to his work. He divides it into three very uneven acts (16 chapters, 31 chapters, 100 chapters). The acts are introduced and completed with a curtain draw and the playing of a shamisen. Between the acts there are interstitial chapters which give a picture of the wider world at the time. (“Interstitial” is the word used by the Fandom wiki. I would not have thought to use it. By the way, I consulted this wiki a bunch to make sure I had my facts straight.) This use of acts by Oda may give some indication of how he sees the organization of the whole work, with its own unevenly divided sections and interstitial arcs that contextualize everything in the world.